Essay 1

Architecture as Textile

Text by Naohisa Hosoo

The first architecture of humanity is said to have been a covering around a human body, not a sturdy structure with a foundation. Humans produced such coverings from animal skin and textiles to protect themselves from harsh weather and predators. The Viennese architect Adolf Loos argues that they are, indeed, the parts that comprise the earliest architecture, and that architectural thinking must begin from these coverings close to a human body, i.e., an interior space. In the context of architecture originating in the West, the emphasis is on the structure that serves as a building’s framework, and interior finishes are dismissed as mere “makeup.” Loos’ argument shocked his contemporaries because of this reversal of the superior-inferior relationship in architecture.

The architect’s task is to create a warm, comfortable space. Carpets are warm and comfortable. Therefore, the architect decides to spread a carpet on the floor and hang up four to form the four walls. But you cannot build a house out of carpets. Both the carpet on the floor and the tapestries on the wall require a structural framework to keep them in the correct position. Devising this framework is the architect’s second task.

Adolf Loos, “The Principle of Cladding”

Adolf Loos’ views were grounded on the architectural theory of Gottfried Semper, a leading German architect of the mid-19th century. Influenced by Goethe’s treatises on nature and art, Semper considered that architecture was created through the dynamic transformation of four elements—the basis of morphogenesis—under diverse conditions. The four elements are “hearth” for holding fire and “roof,” “enclosure,” and “mound” for protecting the hearth. In an explanation of the “enclosure,” Semper points out that, in German, the word wand, meaning a partition wall or wall surface, has the same origin as gewand, a word for a garment. According to him, these terms represent woven (gewebt) or knitted (gewirkt) material, resulting in the word wand. Semper states that the idea of weaving bast fibers to make a mat or a covering arose from a primitive human activity of twig weaving. The concept led to plant fiber textiles, which later came to be used as partitions to divide a room or block the sunlight or cold. Of note is that Semper distinguished a wall surface from a wall, a structure made of stone or brick, and regarded the former as more important than the latter. This is because, in a moderate climate, a wall surface serves as a textile partition, like a carpet, while a wall, a structure, is not required. If architectural thinking must start from a covering closely associated with a human body, or an interior space, then a textile-derived wall surface (wand), which has long been underestimated as “makeup,” embodies the essence of such thought.

Reexamining our own surroundings, we become aware that the attitude that values a covering close to a human body and regards a structure as a supportive framework serving the covering is evident in traditional Japanese architecture, which is composed of shitsurai [the practice of/objects for decorating interior space to show hospitality], not of structure.

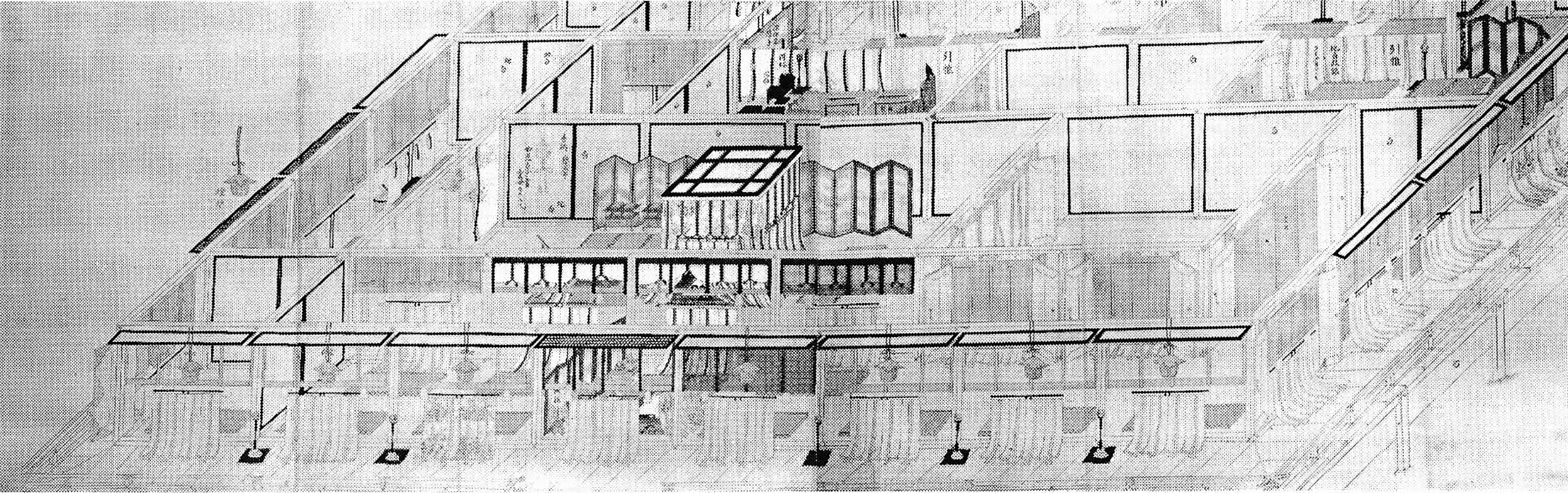

Higashi Sanjo Dono, the residence of successive generations of the Fujiwara family, is considered a representative example of shinden-zukuri architecture from the Heian period. Looking at the house’s restored plan, the space appears empty, with only rows of columns. It is said that necessary “rooms” were created by dividing the spaces with heisho-gu [partitioning devices] and furnishing them with zagu [seating devices]. Shitsurai was a collective term for heisho-gu, such as kicho (a partition with thin silk hanging on a movable stand), kabeshiro (curtains attached to a crosspiece), misu [a reed/bamboo blind], byobu [a folding screen], and tsuitate [a single-panel partition], and zagu, including tatami, enza (a round mat made of woven straw), and shitone (a square mat covered with woven fabric), as well as personal boxes, stands, and shelves of various kinds, but it also included clothes, the first layer of covering around a human body.

Source: Architectural Institute of Japan (ed.), Collected Images of Japanese Architectural History (new revised 3rd ed.), Shokokusha Publishing, 2011, p. 28.

Shitsurai, which is changed according to the season, ceremony, or event, functions as “makeup” that significantly transforms an interior space. Shitsurai as makeup is simultaneously a partition, or wand, and clothes, or gewand, and is elaborately designed because of its proximity to a human body. While these temporary coverings create a glamorous stage for architecture, the structure of a shinden-zukuri building exists discreetly as a framework to protect shitsurai.

Food tastes better when served on beautiful tableware: in the same way, items surrounding our daily lives invigorate our existence as they come in close contact with people. Gio Ponti, known as the father of modern Italian design, was an architect whose design activities were based on the understanding that “objects close to human bodies inspire humanity.” His creative activities transcend different genres of design, ranging from architecture to furniture, bottles, plates, silverware, and opera costumes. What they all have in common is an abundance of unique shapes, colors, and textures that appeal directly to our senses.

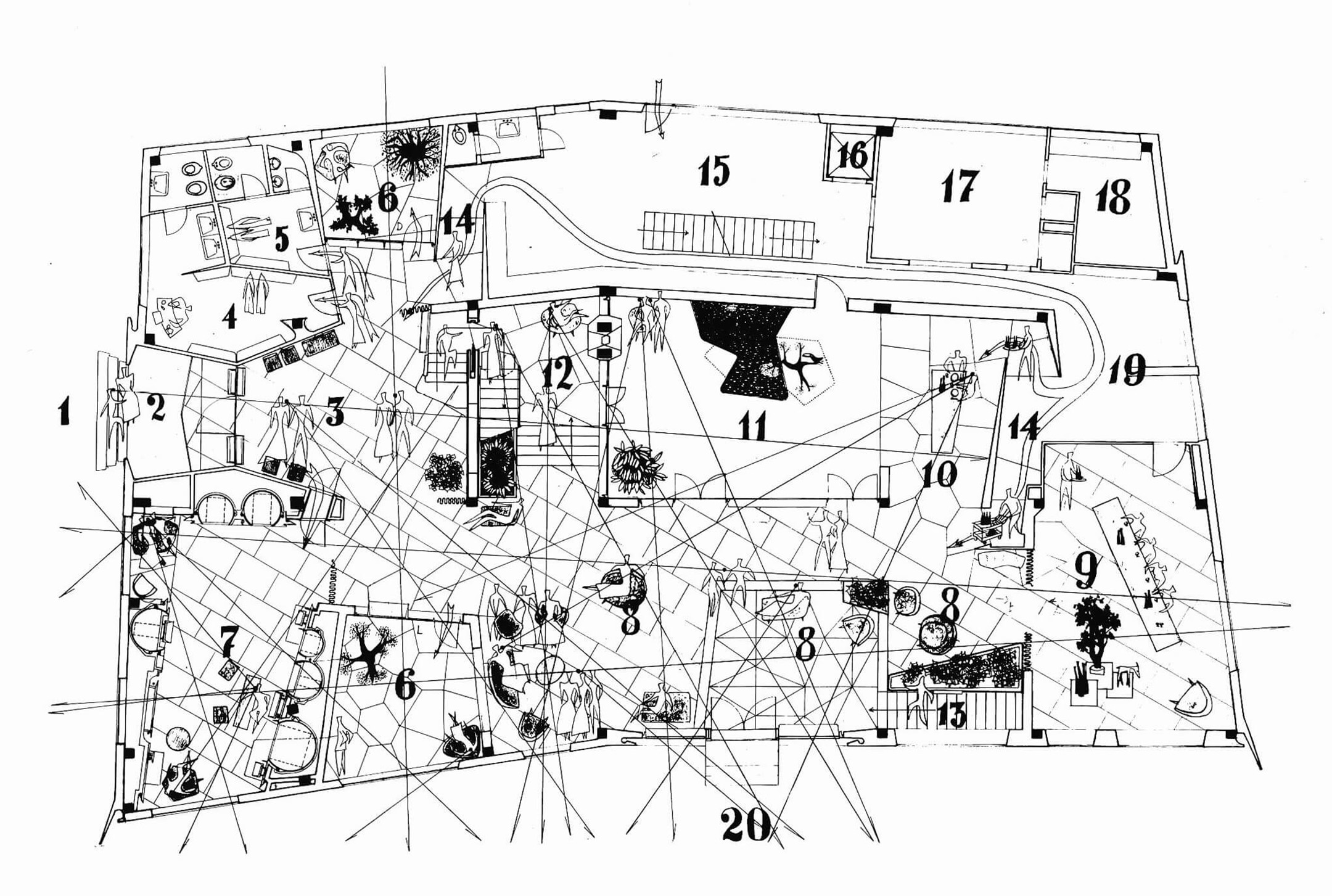

Let’s look at Villa Planchart (1953–1960), designed by Ponti in Caracas, Venezuela. The villa stands on top of a hill and has a pleasant view of the city’s urban district. Ponti’s sketch depicting the building’s relationship with the surrounding topography shows that the view is oriented from the inside to the outside, with the starting point at the architecture. Furthermore, the first-floor plan is filled with intricate drawings of people, items surrounding human bodies, such as furniture and plants, and lines of human circulation and sight, suggesting that Ponti began his design with the human body, developing the architecture from the interior space. The space is adorned with an octagonal dining table, colorful marble details in yellow, white, and green, ceramic tile decorations on the walls, and graphic work on the ceiling. In regard to the interior décor, all surfaces of the floor, walls, and ceiling are covered with energetic, funky elements that make us wonder, dubiously, why such shapes, colors, and textures are used, but the exquisite balance of those elements, indeed, draws out an integrated force from the space. Each funky piece comes in an inexplicable shape and has the appearance of the “other,” a “foreign object,” from another world. However, what is important are the effects achieved by such elements, and unifying these distinct effects into an organic whole creates the texture of the entire interior space.

Source: Fulvio Irace, GIO PONTI, Motta Architettura, 2009, p. 59.

It is important to note that the word mentioned earlier, texture, which signifies a “feel of an object” or a “tactile sensation,” derives from the word “to weave,” so to consider “textiles” as the starting point of architecture is not unreasonable. The weave structure of a textile is multi-layered, formed by threading the weft through the vertically-strung warp at the right angles. Various yarns of different colors and materialities are layered, while embracing each other’s uniqueness, and woven into a unified fabric embedded with the yarns’ diversity and infused with textures. Similarly, at the Villa Planchart, various funky elements—the octagonal dining table, brightly-colored marble, ceramic tile decorations, and graphic work—are woven together, like the various yarns, into an interior space. Thus, the interior décor, a covering that encases a human body, becomes a textile full of textures, and through these textures, it enriches human emotions, just as wearing a beautiful kimono makes you feel happy.

If, as Adolf Loos asserts, architectural thinking must begin from a covering close to a human body, or an interior space, then Gio Ponti undeniably applied Loos’ idea at the Villa Planchart, and the covering, which “creates a warm, comfortable space,” is imbued with textures as textiles. How, then, can we reconsider architecture from this motif of “textile”?

Just as individuals have their own habits and privately carry “otherness” that cannot be identified with one another, individual objects in this world, too, have their own habits. “Textile” is a pursuit that combines foreign objects, which could sometimes repel each other, in a better way by considering their mutual affinity to organically harmonize them and bring out their great power. Such a method is indeed needed in today’s world of myriad conflicts to build a society where we respect our differences and support each other. “Architecture as textile” is a form of architecture composed of objects with distinct functions that make the most out of each other’s character. Such architecture possesses the power to inspire humanity and richly “construct” our lives by enveloping our bodies with a textured covering. A wall surface (wand), shitsurai, and interior décor have long been undervalued as “makeup.” But the heartstrings—found among objects originating from textiles and closely associated with human bodies—are what hold the essence of architecture that underpins our lives.