Essay 2

Genealogy of Construction

Text by Naohisa Hosoo

Seiichi Shirai

A world full of conflicts and fights, not peace, can be described, in a way, as healthy. As long as the existing unfair order is preserved, people cannot complain about issues of discrimination, injustice, and exploitation. Chaos can be a perfect opportunity to object to unjust situations and rectify corrupt relationships. On the contrary, however, it can repeatedly arrive at an ending in which an inequitable order is reproduced as a result of the disorder. Instead of a hierarchy-based, vertically-structured society where people are controlled people, can’t we, people of different origins, beliefs, and personalities, create a free and equal society through collaboration while embracing each other’s individuality? We find a microcosm of our ideal society, called “utopia,” in the architecture of Seiichi Shirai, who continually produced architecture clearly distinct from modernist architecture, whose underlying principles were standardization and uniformity.

Modernist architecture places the primary focus on systematically constructing a building as if it were a machine-made product and making every part replaceable and deindividualized like a soldier in an army, a pawn. The 20th-century capitalist society, with mass production and mass consumption, desired precisely this kind of method. In modernist architecture constructed through the above process, each part is uniform, like a “standardized machine part,” stripped of individuality and treated like a soldier, a pawn, marching in perfect order. The modernist architecture produced by bringing together soldiers possesses the beauty of a highly organized army; therefore, it can be described as “army-like architecture.”

On the other hand, some architectures can be called “multi-protagonist architecture.” In such an architecture, individual parts have their own presence, but none has either primary or secondary status. They are combined in an inevitable way while embracing each other’s individuality. Such an aspect of “multi-protagonist architecture” is suggestive of a society created through lateral cooperation among people who are independent entities. The architecture of Seiichi Shirai falls under this “multi-protagonist architecture.”

In an essay analyzing one of Shirai’s masterpieces, the Shinwa Bank Main Building, Arata Isozaki points out that the essence of Shirai’s architecture is condensed into the peculiarity of its interior ornament.

If it consisted only of furniture by American designers such as Knoll or Herman Miller or, similarly, by contemporary European designers, there would be little need to be amazed. But witnessing a British Victorian-style cabinet next to an Eames lounge chair, with a Flemish convex mirror hung on the wall next to them, and discovering that there is no incoherency among them, or better, that they act as indispensable elements composing the tense space as if they were the heart of the original plan, I couldn’t help but be overwhelmed.

Arata Isozaki, “The formation of ‘Seiichi’s taste,’ constructed by committing his entire existence on momentary choices while confronting naked concepts amid frozen time, and the meaning of Mannerist ideas in contemporary architecture”

Furniture and furnishings are not arranged uniformly in one style. Instead, objects from all ages and places with different backgrounds and looks are exquisitely balanced, with each object exuding its presence, giving us the impression of watching a multi-protagonist drama. This “multi-protagonist drama” is present not only in the interior ornament but also in every part composing the architecture of Seiichi Shirai. A wall covered with light-purple fabric with travertine strips inserted in places, and a greige carpet. A mass of white travertine penetrated by a cylindrical shaft of polished black granite, and gold letters carved on the shaft’s surface. Individual elements appear Westernized and emanate an air of foreignness. Yet, dramatically combined and balanced, their aesthetic powers that touch human sentiment are brought out. What is noteworthy is that these powers derived from the relationships among objects are purposely used to guide human emotions toward a particular direction. Just as the space in a courthouse evokes a feeling of solemnity, the space in a house offers relaxation, and the space in a bar creates a lively atmosphere, Shirai’s architecture inspires its visitors to reach the height of their emotions. The effect resembles theatrical expressions used by actors, such as lines, facial expressions, and gestures, to induce the audience’s emotions to feel happy or sad. Incidentally, Shirai is known to have been a member of a theater company called Élan Vital while studying at the Kyoto School of Arts and Crafts.

Seigo Motono

In his younger days, Seiichi Shirai graduated from a department of zuan at the Kyoto School of Arts and Crafts. Zuan refers to what we now call design, and the prewar zuan course in which Shirai studied covered all aspects of design, including architecture. Seigo Motono, Shirai’s professor who is known for inviting Bruno Taut, an admirer of the Katsura Imperial Villa, to Japan, was an architect and the founder of the International Architectural Association of Japan. However, his interest was not limited to architecture; he sought to design all things related to daily life, from interior to furniture to stage to clothing.

In his commentaries on the declaration of the International Architectural Association of Japan, founded in Kyoto in July 1927, Motono wrote the following.

Declaration 1. We seek to fundamentally resolve the course of architecture based on the existence of humanity

The existence of humanity—the question begins here. What is the heart of human existence? Is it a collection of matter, is it an idea, or is it the will of God? Exploring these queries is not our objective. We are faced with an undeniable fact of human existence. Before examining what lies at the core, we must admit that there is only one fact. This is where we base our belief. (...) Given this belief, all isms vanish. Birds build a nest. They seem to have no science, philosophy, or religion. But they have a dwelling that conforms to their living. We will make every effort to pursue the nest for us humans. Science, philosophy, and religion—everything will serve some purpose to this end.

Seigo Motono, “The declaration by the International Architectural Association of Japan and commentaries on the manifesto”

A bird builds its nest by exerting influence on nature. And the nest cooperates with the bird to enrich its existence (so it can reproduce). In the same way, Seigo Motono was consciously thinking about creating a nest that could improve human existence itself. Having no fur or strong fangs and claws, and being slow-footed, humanity is physically vulnerable, but its existence is transformed by manipulating nature to create various objects and working with them. Riding a bicycle allows us to move faster, wearing cashmere knitwear protects us against the cold, and laying on a bed lets us rest our bodies. Wearing a luxurious watch makes us feel invincible, wearing a beautiful necklace elevates our feelings, and putting on makeup gives us confidence. Working with objects allows humankind to transform, and accumulating such transformations leads to the creation of human existence.

Seigo Motono is positioned in history as an avant-garde architect at the forefront of his time in the 1910s and 20s. The technology-based, unadorned design pursuing functionality and rationality is the expression of modern architecture. However, Motono’s own residence, which was completed in 1924, is recognized for realizing, for the first time in the world, an exterior wall design with bare concrete blocks. But unlike Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye (completed in 1931), which represents the five points of modern architecture (pilotis, roof garden, free design of the ground plan, horizontal window, free design of the façade), the Motono House lacks an overarching design concept that could function as propaganda. Rather, Motono’s essence dwells in the expressions of his architecture’s small parts, to which its users can feel attached.

The warm texture of exterior wall concrete blocks, an iron fence with vertical members welded to jut out from the top and bottom of the four-sided frames, a brick-covered column defining the entrance porch, a fireplace adorned with a grape-patterned ornament, a staircase that invites us to climb up, and furniture that is geometric and adorable at the same time.

Motono was likely aware that objects’ expressions that would evoke a sense of attachment were, indeed, what possessed the power to inspire humanity. Just as wearing one’s favorite clothes lifts one’s spirits, each small element of architecture enriches its inhabitants’ state of being by organically interacting with them and being used habitually. In fact, Motono only produced about ten architectural works. His other works ranged widely, including interior design for ships, furniture and stage design, clothing, and doll making, so some may think he was uncommitted to architecture and engrossed in other arts. However, while the genre of his work lacked consistency, his idea, “working with objects transforms humankind and builds human existence,” seems to be embedded throughout his wide-ranging works beyond architecture.

Theater gives us a glimpse of how people can become someone else through externally given conditions such as stage sets, casting, words, and costumes. Between 1923 and 24, Motono designed many stage sets for Élan Vital, a theater company that Seiichi Shirai would join in later years. In The German Ideology, Karl Marx wrote: “Life is not determined by consciousness, but consciousness by life.” Motono, too, stood on materialism that claimed a person does not control objects, but objects have the power to determine even the human consciousness. Lastly, it should be noted that Motono was an organizer of the Association of Friends of the Soviet, which introduced Soviet Russia’s initiatives of the time to build a new society.

Rodchenko

In 1917, the poet Mayakovsky composed the following poem on the occasion of the Russian Revolution that overthrew the tyrannical and unjust order imposed by the tsar.

Citizens

Today, a thousand years of “past” is collapsing.

Today, the world’s foundation is being revised.

Today,

down to the last button of our clothes

we are remaking our life anew

— Mayakovsky, “Revolution”

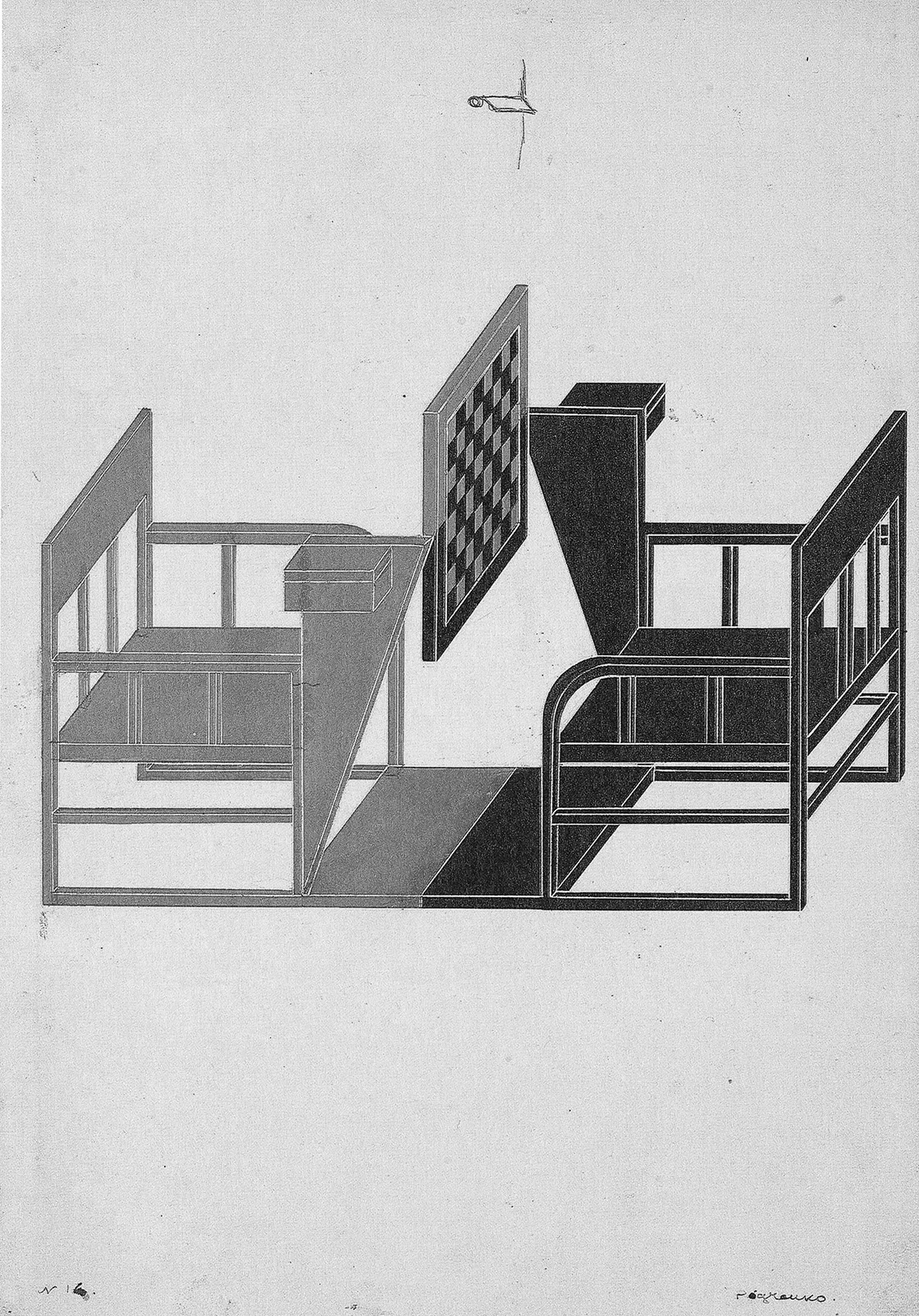

In the early Soviet period, when the country was ablaze with the passion for building a new society, Aleksandr Rodchenko, a colleague of Mayakovsky’s and a designer, criticized capitalist society, which ephemerally used and disposed of popular commodities. Rodchenko believed that favorably treating such items as his “comrades,” with which he spends his life, instead of as disposable “slaves,” would bring a truly prosperous life. To realize this, he designed multi-functional, adjustable furniture that could flexibly respond to various spaces and uses and change with people. A table whose size and form can be adjusted according to the number of users, a wardrobe that also serves as a cupboard, a foldable dining table, a chair that also serves as a sofa, and a retractable bed—such shape-shifting pieces of furniture foster communication between the furniture and its users, and as a result, activate and stimulate people. Furniture is usually considered to only function like a servant of humans, but the furniture conceived by Rodchenko was not intended to play such a role but to work with humans as an equal partner or “comrade” to contribute to the construction of a truly prosperous society.

Source: ALEKSANDR RODCHENKO & VARVARA STEPANOVA: Visions of Constructivism, Asahi Shimbun, 2010, p. 100.

Rodchenko is known for his multi-genre creative activity based on the method called “construction,” which refers to the making of a form stripped of all unnecessaries and in which parts and the whole are inevitably linked. Its functional power is brought out by logically organizing each part. Through this method, Rodchenko designed various objects that richly constructed human life, from furniture, or “comrades,” to tableware, clothes, photography, and graphic design. Moreover, he, too, was deeply involved in dramatic art.

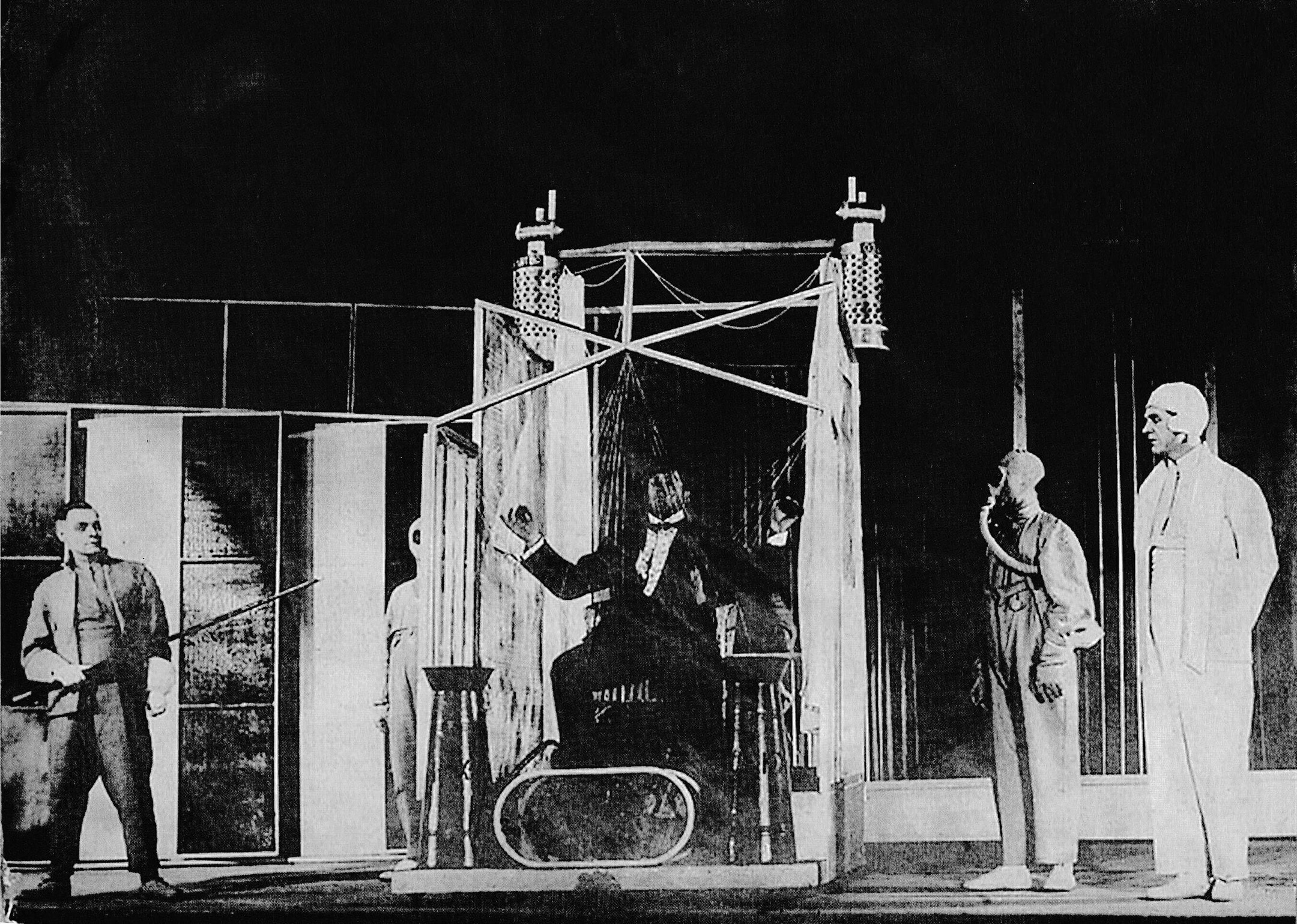

In 1929, 12 years after the Russian Revolution, with the dream of a new, ideal society fading, Mayakovsky published his play The Bedbug. In the Soviet Union at the time, many of its citizens were seeking petty-bourgeois luxury under the new, post-revolutionary economic policies, and the ideals of socialism were being emasculated. The play’s snobbish protagonist, who symbolizes such social conditions, travels through a time warp 50 years into the future, to 1979. In the future society that has achieved a “truly prosperous life,” the protagonist is diagnosed as an unsound “bedbug” that harms humanity and is confined in a zoo. Rodchenko was asked by Mayakovsky to design the future society’s stage set for this satirical play, which depicts the future Soviet as a society stripped of all unnecessaries and in pursuit of only functionality, without paper money, romantic relationships, beer, dance, handshakes, or suicide. Rodchenko intended to compose an image of such a society using frame objects in place of ornaments and backdrops, and materialistic costumes made of industrial waterproof fabrics.

Source: ALEKSANDR RODCHENKO & VARVARA STEPANOVA: Visions of Constructivism, Asahi Shimbun, 2010, p. 115.

However, Mayakovsky not only satirized the condition in 1929 but also implied that there would be no salvation in the future society of 1979. This is evident because, in the future “utopia,” the scantiness of life is revealed paradoxically through the pursuit of functionality alone. The following year, under the tyrannical regime of Stalin, who was considered the reincarnation of the tsar, Mayakovsky was driven to suicide, and his dream of “remaking life anew” came to a complete end.